One Register to Rule them All: what Stats NZ is planning behind closed doors

Misuse of personal data at Manurewa Marae is just the tip of the iceberg in what has been revealed as a monster data-centralising project.

Part one of a four part investigation by Bonnie Flaws. Read parts two, three and four.

StatsNZ is creating a Persistent Unique IdentIfier (PUI) for each citizen to track them over time in an Integrated Statistical Data System - or 'Statistical Register’.

The new system will link business, location and population registers giving a nearly complete picture of a persons life over time

The data in this register will be updated in real time as it becomes available, moving away from data ‘snapshots’ that only show a moment in time

A Stats NZ insider is concerned this power will be abused

An explanation of terms can be found here

The scandal we know about

Data is digital gold, as we’ve recently seen firsthand.

The Public Service Commission investigation into misuse of data at Manurewa Marae revealed that voters on the Māori Roll in the Tāmaki Makaurau electorate were exploited and their data commandeered for what looks like political gain.

It’s alleged that personal data collected during the 2023 Census and Covid-19 vaccination efforts was misused to benefit Te Pāti Māori's election campaign.

Former chief executive of Stats NZ, Mark Sowden, rightly fell on his sword for not putting in place appropriate safeguards and working on an inappropriate “high trust model”.

It was also revealed that Health NZ failed to ensure sensitive health data was properly safeguarded at the marae. The Public Service Commission found that a "gate was left open”. Contracts lacked provisions for audits or compliance checks, allowing outside providers unrestricted access to files. In the aftermath, the agency urgently revised contracts to enable audits and conflict-of-interest checks.

Despite following privacy laws, Health NZ never ensured providers met security standards. While no misuse of data collection has been confirmed, authorities stress the need for stricter data protections to maintain public trust in health information security.

All this calls into question the quality of leadership and the depths of public service integrity. After the reports came out, the Democracy Project’s Bryce Edwards said in a scathing assessment of our institutions:

“We are often told that there is no corruption in New Zealand, and that our public service and electoral system are robust and free from manipulation and conflicts of interest. But the two official reports released yesterday about the allegations of misuse of resources and data by organisations aligned with Te Pāti Māori should put such myths to bed.”

Well, the dust hasn’t settled yet.

The IDI: the database you might have heard of (but probably not)

With all that incompetence and, perhaps, corruption on the table, consider the inherent danger of a Stats NZ project to create a unique ID for each and every New Zealand citizen currently underway.

The agency has not exactly front-footed the public communications on what it’s doing.

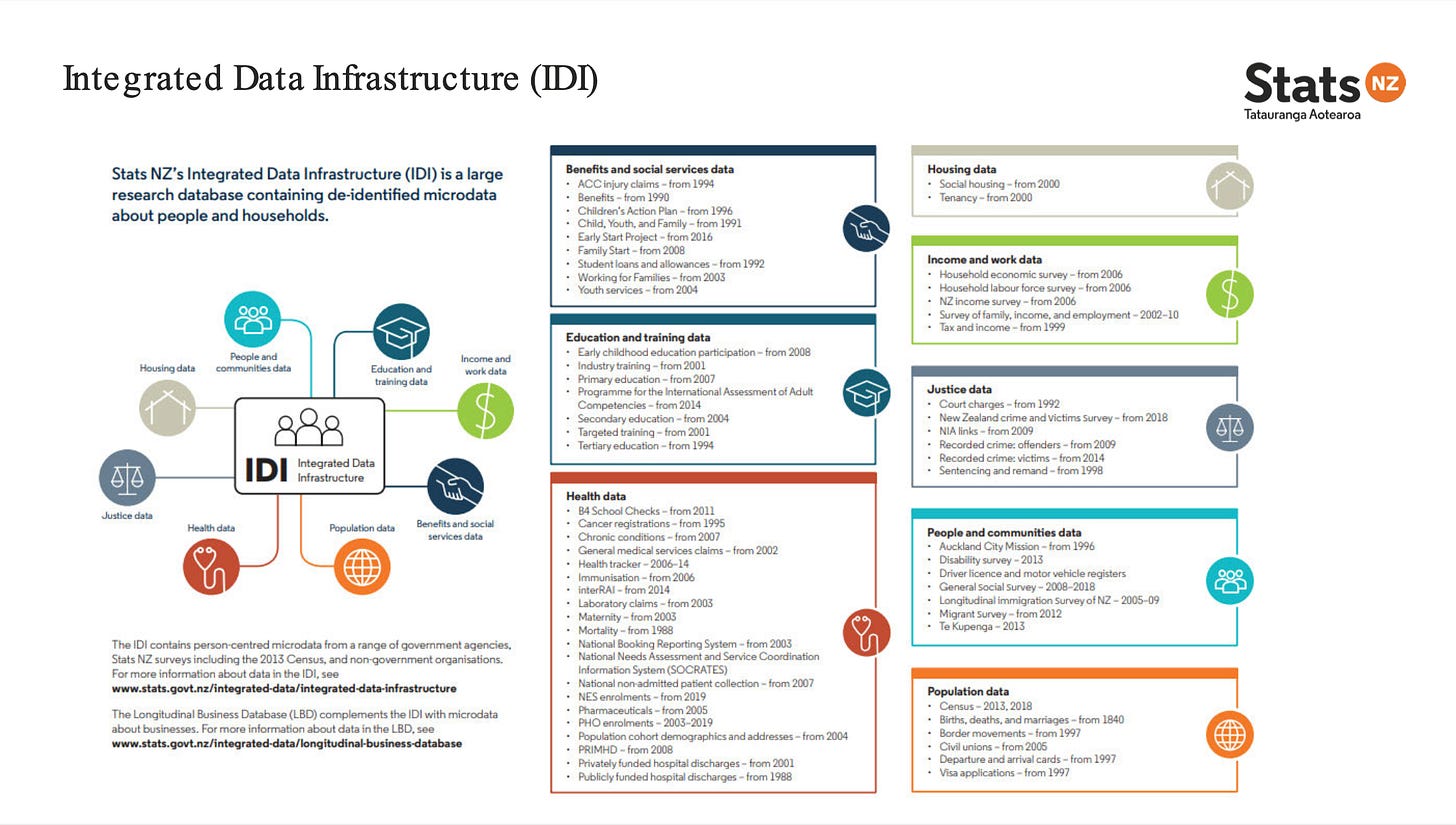

You may have already heard of the Integrated Database Infrastructure (IDI), a person and household database that has been developed since 2011, which collects de-identified data from tax, social welfare, the justice system, education and health records. It has attracted scrutiny from journalists and academics for holding this information, which is justified as a tool for research and public policy.

Along with data from the Justice Department, IRD, Ministry of Health, Ministry for Social Development, Ministry of Education, Kainga Ora, the IDI also compiles its people profiles from Police crime records and many other smaller sources.

It was developed under the 1975 Statistics Act, but this was replaced in 2022 by the Data & Statistics Act, which has been a controversial piece of legislation from the off, drawing criticism from two former Government Statisticians, a former Prime Minister and the Council for Civil Liberties. More to come on that, but suffice to say it has never been widely consulted on.

Hailed as an incredible research tool, it’s a double edged sword. Integrated Data played a big role in the government's response to Covid-19, including in projects run by Shaun Hendy’s team at the University of Auckland, which fed directly into the National Crisis Management Centre’s response. Treasury also used it to model the effects of different lengths of lockdown on schools, the economy and businesses, while MBIE used it to analyse the effects of lockdown on business and workers - cold comfort for many no doubt, when those policies are considered to be at the heart of the country’s increasing lack of social cohesion.

An Stats NZ insider who spoke to me on condition of anonymity believes that if the public knew more about what the IDI holds about them, they might be nervous about the potential for government overreach.

According to the source, getting IDI access does have a lot of controls and requires interviews and confidentiality training to access. But it also has weaknesses such as a lack of auditing for the researchers who might be accessing it.

Usually, a research project gets access to only a specific dataset for analysis, but sometimes a researcher might be on multiple projects over the years and accumulate access to multiple datasets, they say.

“No one checks to see if they are using their approved datasets for a specific project or not. It is up to the integrity and seniority of the researcher.”

While researchers are required to sign NDAs, more than 100 data breaches had already occurred by 2023. I’ve asked Stats NZ for more up to date figures but they were unable to get back to me in time for publication.

Also of concern, research from 2019 found that applications to use the IDI for research are reviewed internally by Stats NZ, with no mandatory external peer review or ethical approval across sectors. Furthermore, ethical standards for using IDI data vary across universities, government departments and private research entities.

All of Stats NZ data gathering powers rely on social license. But surveys have shown that there is actually low public trust around Stats NZs ability to keep data safe or even that it considers the public’s views in its decision making.

However, there may be considerably more reason to question the social license Stats NZ relies on today.

The Everything Database: person-level tracking in real time, all the time

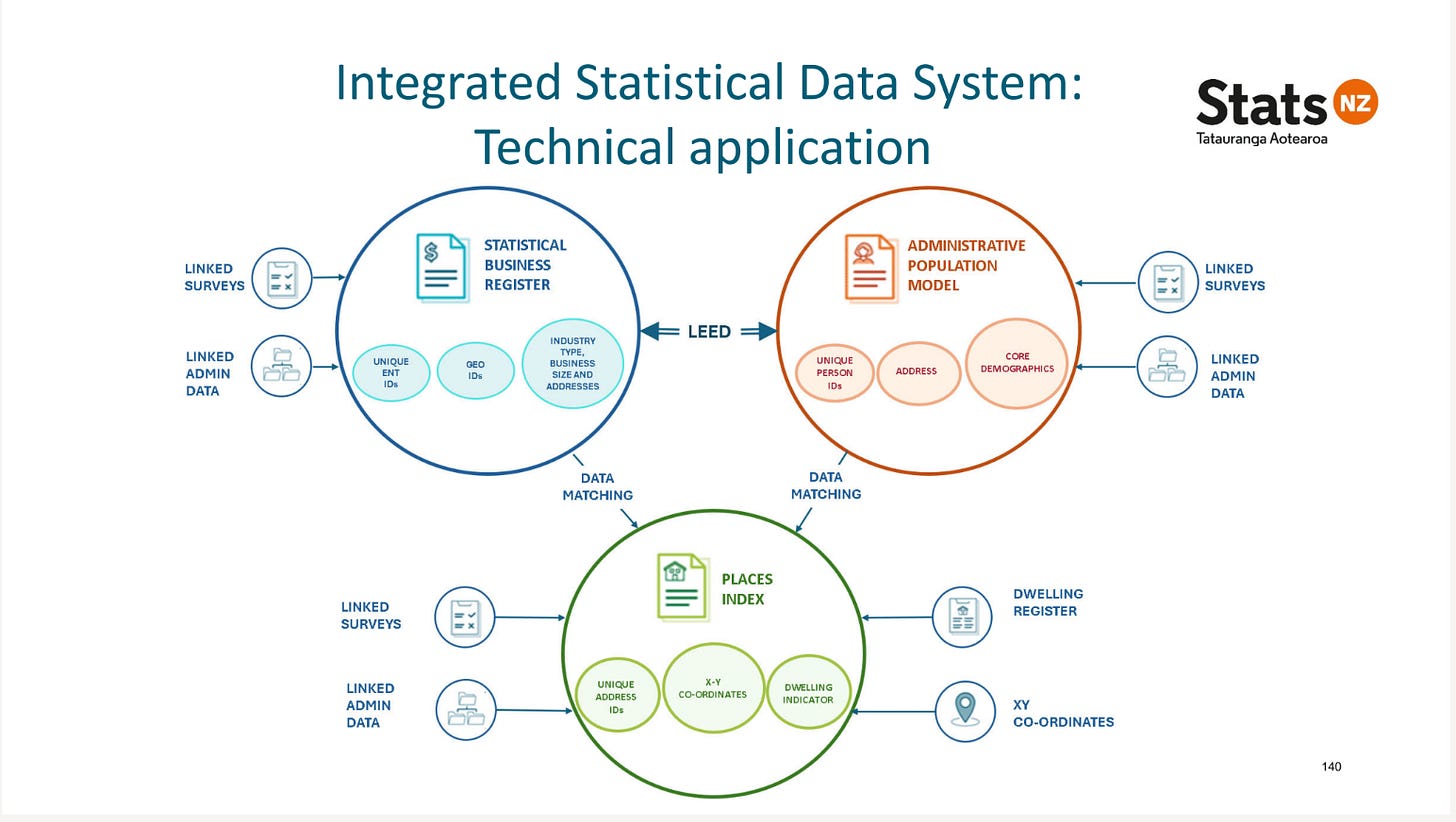

A multi-part Official Information Act request from April 2024 has revealed that since 2022, an initiative called the Statistical Register has been underway with the goal of linking an upgraded version of the IDI with an existing location register (a list of addresses and addressable objects) and a 30-year-old business register (containing information on business profits, sector, age and size) via IRD tax data. Development consultants Allen + Clarke describe it as “unlocking high value”.

In sector jargon, this Statistical Register would be the realisation of an ‘Integrated Statistical Data System’. What I have euphemistically called the ‘everything database’, because it is not far short of that. And as we will see, there is the potential to add all kinds of other data streams to this register, such as social media, supermarket spending or telecoms data for example.

“The amount that could be controlled when you know someone’s political views and address and workplace and family history might be too much power for one organisation,” the insider says.

The IDI becomes the IPS

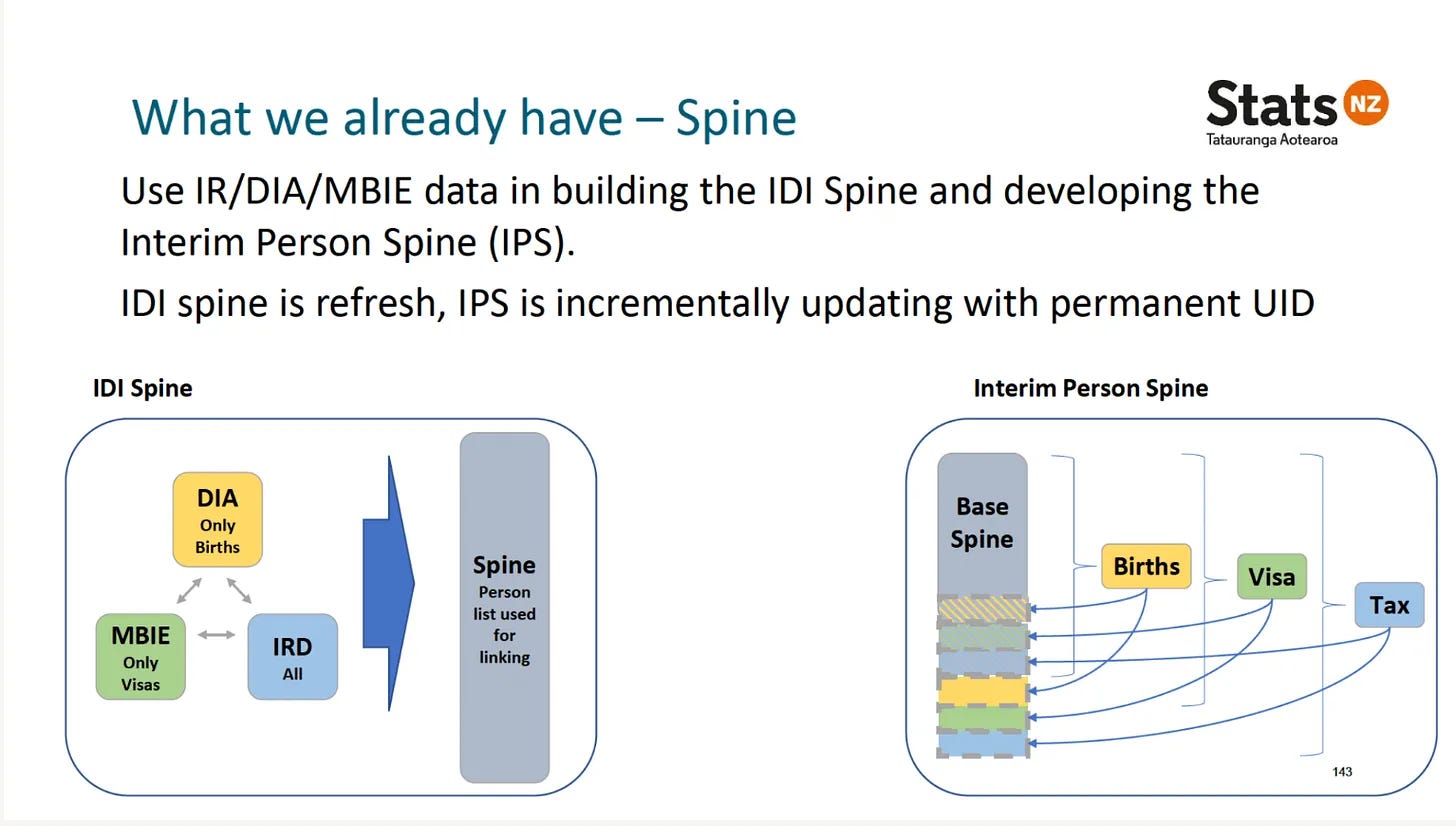

To go a bit deeper, OIA responses further reveal that before Stats NZ can do the final ‘link-up’ of their registers, it must upgrade the current IDI, which is really only a prototype for what they want to do with the statistical person register.

It is implementing what they call an Interim PersonSpine (IPS), as an improvement to the current IDI prototype, to track people. Basically a population register.

To do this, it is moving from scheduled data updates to the collection of real-time data. Currently, the IDI uses refresh timelines - moments in time when the data on a person is updated, usually three times a year, and then probabilistically linked via a ‘spine’, usually the name and birthdate, which most agencies collect.

Each time the data is collected and updated Stats NZ creates a new unique identifier for every individual in its anonymisation process, so that it can’t make a longitudinal profile for each person using past data sets.

However, the IPS does away with the ‘refreshes’ to ongoing real-time updates, as and when the information from government agencies gets supplied to StatsNZ.

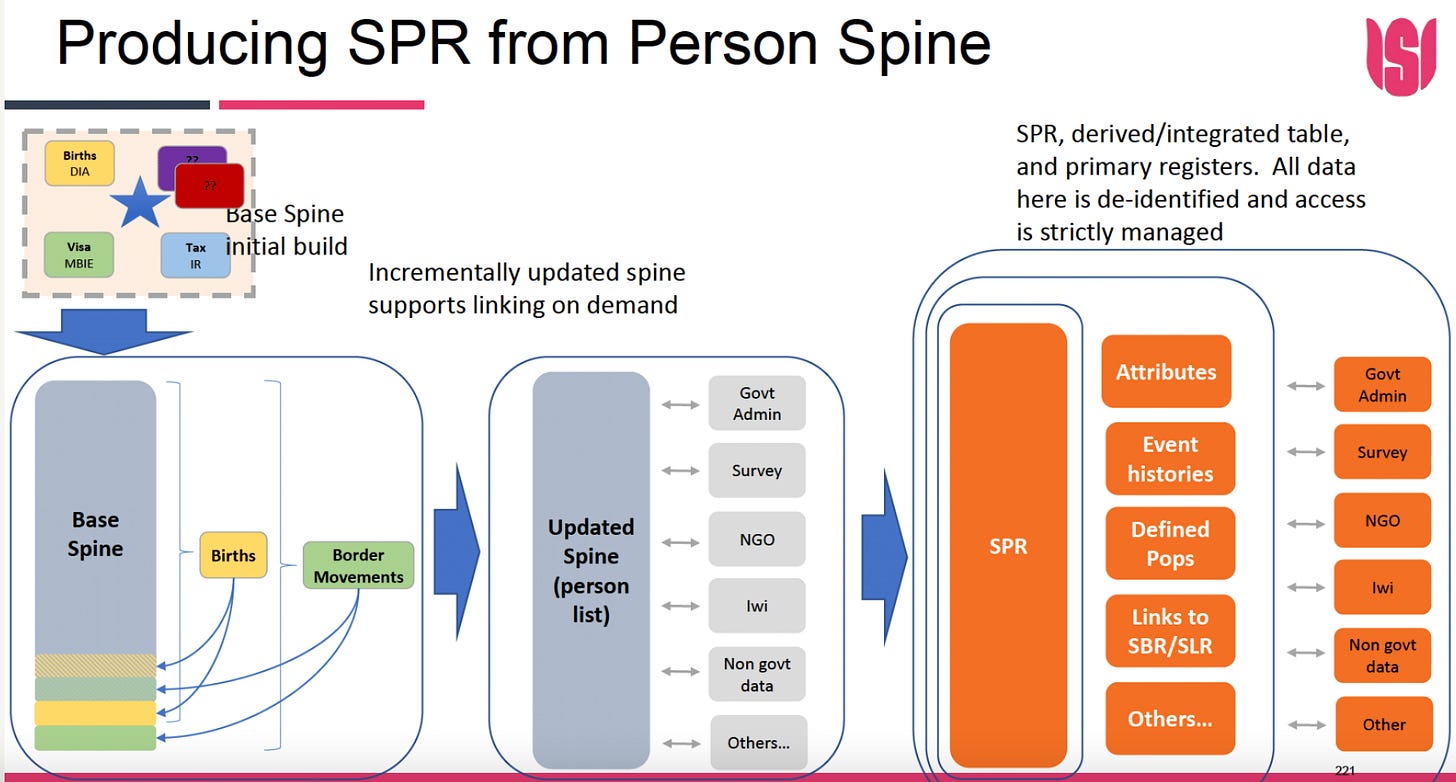

Persistent Unique Identifier

Here’s the kicker:

Once the business and location data are linked to the new IPS, they will have succeeded in creating a central register, with each person represented by a unique ID that can be tracked over time and tell a story about a person’s whole life, and even to track a person’s life events from birth. It’s referred to as a ‘Persistent Unique Identifier’ (PUI) in sector jargon.

The end result is the Statistical Register (everything database) plus a permanent digital tag for every person.

The eye of Sauron on everyone one of us, all the time, whether we want it or not.

Follow up questions were put to Stats NZ but they are now treating it as an OIA request and were not able to respond in time for publication. I will update readers with any response I receive in due course.

Part two will be published on Saturday April 19.

Republication with permission only.

Well researched and informative, thank you. I know I’m still a leftie when I consider something like this and conclude it could be beneficial. Some people I know would only see the dangers. Obviously we need adequate checks and balances for data collection on this scale.